- Home

- Leslie Berlin

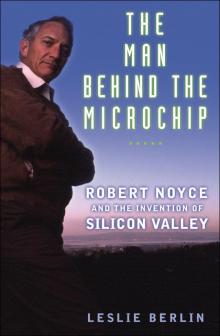

The Man Behind the Microchip

The Man Behind the Microchip Read online

THE MAN BEHIND THE MICROCHIP

He who lives to see two or three generations is like a man who sits some time in the conjurer’s booth at a fair, and witnesses the performance twice or thrice in succession. The tricks were meant to be seen only once; and when they are no longer a novelty and cease to deceive, their effect is gone.

Arthur Schopenhauer, “On the Sufferings of the World”

THE MAN BEHIND THE MICROCHIP

Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley

LESLIE BERLIN

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that

further Oxford University’s objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright © 2005 by Leslie Berlin

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berlin, Leslie, 1969–

The man behind the microchip : Robert Noyce and the invention of Silicon Valley / Leslie Berlin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-516343-8

ISBN-10: 0-19-516343-5 (alk. paper)

1. Noyce, Robert N., 1927–. 2. Electronics engineers—United States—Biography.

3. Santa Clara Valley (Santa Clara County, Calif.)—History. I. Title.

TK7807.N69B47 2005

621.381’092—dc22

2004065494

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

To Rick, Corbin, and Lily

My beloved ones

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Adrenaline and Gasoline

2 Rapid Robert

3 Apprenticeship

4 Breakaway

5 Invention

6 A Strange Little Upstart

7 Startup

8 Takeoff

9 The Edge of What’s Barely Possible

10 Renewal

11 Political Entrepreneurship

12 Public Startup

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Appendix A Author’s Interviews and Correspondence

Appendix B Robert Noyce’s Patents

Index

Acknowledgments

One reason it took me several years to write this book was that before I could even start, I needed to create my own archive. Noyce’s papers were not collected—he freely admitted he was “very sloppy in record-keeping”—and many important documents in the history of Silicon Valley have been lost, forgotten, or (I was dismayed to learn) destroyed. In the process of copying or gathering materials from basements and archives around the country, I have been fortunate to encounter more than a hundred people who were willing to share their documents and their memories of Noyce and the early days of the Silicon Valley semiconductor industry. The names of those generous people appear in Appendix A; to each of them, I am endlessly grateful. In addition, I would like to express particular gratitude to the following people who met with me multiple times or shared useful documents with me: Julius Blank, Roger Borovoy, Warren Buffett, Maryles and Mar Dell Casto, Ted Hoff, Paul Hwoschinsky, Steve Jobs, Jean Jones, Jim Lafferty, Jay Last, Christophe Lécuyer, Regis McKenna, Gordon Moore, Adam Noyce, Bill Noyce, Gaylord Noyce, Penny Noyce, Polly Noyce, Ralph Noyce, Karl Pedersen, Evan Ramstad, T. R. Reid, Daniel Seligson, Robert Smith, Charlie Sporck, Bob and Donna Teresi, and Bud Wheelon. Donald Noyce, Robert Noyce’s older brother, was an amateur historian and—thank goodness—an inveterate packrat. Before he died quite unexpectedly in November 2004, he shared his collection of family memorabilia with me, a gift that contributed immeasurably to the early chapters of The Man Behind the Microchip.

Ann Bowers deserves special thanks of her own. This biography has been an entirely independent undertaking, but it would not be the book it is without her support. She sat through many hours of interviews, helped me contact key players in Bob Noyce’s life, and granted me access to boxes of papers and photos—all without imposing any limitations of any kind on my research or writing.

In addition, the following experts merit thanks for their guidance: Polly Armstrong, Maggie Kimball, Henry Lowood, and Christy Smith at the Stanford Special Collections; Tim Dietz and Annie Fitzpatrick at Dietz and Associates; Leslie Gowan Armbruster at the Ford Motor Company archives, Ford Motor Company; Mickey Munley and Catherine Rod at Grinnell College; Daryl Hatano at the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA); Marilyn Redmond at SEMATECH; John Clark at National Semiconductor; and the incomparable Rachel Stewart at the Intel archives and museum. The book also benefited from materials made available to me at the following archives and repositories: the Center for History of Physics, American Institute for Physics; the California History Center, De Anza College; the Electrochemical Society; the Grinnell Room, Stewart Public Library, Grinnell, Iowa; the Hewlett-Packard archives, Hewlett-Packard Corporation; the IEEE History Center Oral History Collection; the Libra Foundation, Portland, Maine; the Institute Archives and Special Collections, MIT Libraries; the MIT University Physics Department; the Pacific Studies Center, Mountain View, California; and the Stanford News Service.

Many thanks to members of the Stanford biographers seminar; to Alex Kline; to two anonymous readers selected by Oxford University Press; to Liz Borgwardt, David Jeffries, and Ron Newburgh, who read early chapter drafts; to Jose Arreola, a friend and physicist who spent more than an hour talking to me about Noyce’s doctoral dissertation; to David M. Kennedy, whose review of the manuscript did more to improve it than he will ever know; and to Ross Bassett, not only a fantastic reader but also the author of an excellent work of semiconductor history.

My editor at Oxford, Susan Ferber, always asked the right questions and pushed me just as much as I needed. Donald Lamm, my agent, has helped me through every step of this process. My parents, Steve Berlin and Vera Berlin, and my sisters Jessica and Loren have been endlessly inquisitive and supportive.

The Life Member’s Fellowship in Electrical History from the IEEE and a Franklin Research Grant from the American Philosophical Society supported the research for The Man Behind the Microchip; grants from the Andrew P. Mellon Foundation, the Charles Babbage Institute, and Stanford University funded earlier research for my doctoral dissertation, some of which has been incorporated into this book.

A special thanks to the History Department at Stanford University, where I have worked for the past two years as a visiting scholar in the Program in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Two professors in the department—Tim Lenoir and David M. Kennedy—have been thinking with me about Robert Noyce since 1997, when they began advising my dissertation on Noyce’s career. I have long c

onsidered Tim and David mentors and am now honored to count them among my friends, as well.

In addition, I am immensely grateful to the staff of Discovery Children’s House, as well as to two wonderful young women—Michelle Casady and Megan Baldwin—who cared for my children for the hours each week that I devoted to research and writing.

The final thanks—and the word seems so inadequate—goes to my husband, Rick Dodd, the great love of my life and my partner in every possible way. From tutoring me on the finer points of semiconductor electronics, to running to the copy store, to reading the manuscript at midnight, to making the kids’ breakfasts the next morning, he did everything possible to ensure that this book had the best chance of success.

THE MAN BEHIND THE MICROCHIP

Introduction

Bob Noyce took me under his wing,” Apple Computer founder Steve Jobs explains. “I was young, in my twenties. He was in his early fifties. He tried to give me the lay of the land, give me a perspective that I could only partially understand.” Jobs continues, “You can’t really understand what is going on now unless you understand what came before.”1

Before Intel and Google, before Microsoft and dot-coms and Apple and Cisco and Sun and Pixar and stock-option millionaires and startup widows and billionaire venture capitalists, there was a group of eight young men—six of them with PhDs, none of them over 32—who disliked their boss and decided to start their own transistor company. It was 1957. Leading the group of eight was an Iowa-born physicist named Robert Noyce, a minister’s son and former champion diver, with a doctorate from MIT and a mind so quick (and a way with the ladies so effortless) that his graduate-school friends called him “Rapid Robert.” Over the next decade, Noyce managed the company, called Fairchild Semiconductor, by teaching himself business skills as he went along. By 1967, Fairchild had 11,000 employees and $12 million in profits.

Before the Internet and the World Wide Web and cell phones and personal digital assistants and laptop computers and desktop computers and pocket calculators and digital watches and pacemakers and ATMs and cruise control and digital cameras and motion detectors and video games—before all these, and the electronic heart of all these, is a tiny device called an integrated circuit. The inventor of the first practical integrated circuit, in 1959, was Robert Noyce. It was one of 17 patents awarded to him.

In 1968, Noyce and his Fairchild co-founder Gordon Moore launched their own new venture, a tiny memory company they called Intel. Noyce’s leadership of Intel—six years as president, five as board chair, and nine as a director—helped create a company that was roughly twice as profitable as its competitors and that today stands as the largest producer of semiconductor chips in the world.

But Noyce believed “big is bad”—or if not downright bad, at least not as much fun as small companies in which “everyone works much harder and cooperates more.” When he left daily management at Intel in 1975, he turned his attention to the next generation of high-tech entrepreneurs. This is how he met Jobs. This is how he came to serve on the boards of a half dozen startup companies and informally provide seed money to many more. He did not think that all these companies would succeed—he filed his paperwork for several of them in shoe boxes that he kept in his closet—but he strongly believed that by investing, he was doing his part, as he put it, to “restock the stream I’ve fished from.”2

Noyce was constitutionally unable to sit on the sidelines of any operation with which he was involved. He once called his invention of the integrated circuit “a challenge to the future,” and turning away from the television interviewer, he stared straight into the camera to speak directly to the viewers: “Now let’s see if you can top that one,” he said, flashing a smile. At a father-son baseball game, which the dads traditionally allowed the boys to win, Noyce hit the very first pitch out of the park. “My poor father couldn’t help himself,” recalls his daughter Penny, who was in the stands that day. “He always threw himself entirely into the activity at hand—in whatever he did, he tried to excel.”3

Robert Noyce’s favorite ski jacket featured a patch that declared “no guts, no glory.” It was a fitting motto for a man who flew his own planes, chartered a helicopter to drop him on mountaintops so he could ski down through the trees, rode a motorcycle through the streets of Bali in the middle of a thunderstorm, and once leapt with his skis off a 25-foot ledge into deep powder, exultant because he “had never jumped off a cliff into that much snow.” His powers of persuasion were legendary. In 1963, he convinced the notoriously conservative board of one of his companies to start the semiconductor industry’s first offshore manufacturing facility—at a site that was then completely under water, soon to be reclaimed from the bay by the government of Hong Kong. He talked a carload of traveling companions into joining him for a dip in a brackish Tibetan river, murky and, just a bit upstream, filled with crocodiles. He inspired in nearly everyone whom he encountered a sense that the future had no limits, and that together they could, as he liked to say, “Go off and do something wonderful.” Recalls Intel’s former chief counsel, “He was like the pied piper. If Bob wanted you to do something, you did it.”4

Like so many others who spend their lives in the limelight, Noyce was an intensely private man. “He was the only person I can think of who was both aloof and charming,” says Intel chairman Andy Grove. “I don’t know how Bob kept you away, but you just didn’t know anything about him. And this is the guy who would go down on one knee to adjust my skis, put my chains on, when I was a nobody.”5

To be sure, Noyce’s was not a simple personality. A small-town boy suspicious of large bureaucracies, he built two companies that between them employed tens of thousands of people, and he spent many years working through the maze of federal politics after he helped launch the Semiconductor Industry Association, today one of the nation’s most effective lobbying organizations. He was a preacher’s son who rejected organized religion, an outstanding athlete who chainsmoked, and an intensely competitive man who was greatly concerned that people like him. He was worth tens of millions and owned several planes and houses but nonetheless somehow maintained a “just folks” sort of charm: you half expected him to kick the ground and mutter “aw shucks, you guys,” when his hometown declared “Bob Noyce Day” or an elite engineering group named him the first recipient of an award many called the Nobel Prize for Engineering. Recalls Warren Buffett, who served on a college board with Noyce for several years, “Everybody liked Bob. He was an extraordinarily smart guy who didn’t need to let you know he was that smart. He could be your neighbor, but with lots of machinery in his head.”6

It is easy to imagine Noyce, tuxedoed, smiling shyly, and desperately wanting a cigarette, in October 2000, when, had he lived, he undoubtedly would have shared the Nobel Prize for Physics awarded to his integrated circuit co-inventor, Jack Kilby. Amazingly, this is the second Nobel Prize that Noyce might rightfully have won. The first was in 1973, when a Japanese physicist named Leo Esaki was one of three recipients of the physics prize. Esaki was cited for his pathbreaking work on the tunnel diode, a device that provided the first physical evidence that tunneling, a foundational postulate of quantum mechanics, was more than an intriguing theoretical concept. Noyce had written a complete description of the tunnel diode nearly a year and a half before Esaki published his work in 1958. The two men’s research was thus happening almost simultaneously on opposite sides of the Pacific. Noyce had not published his ideas, however, because his boss, the Nobel laureate William Shockley, discouraged him from pursuing them.

Beginnings fascinated Noyce. He could imagine things few others could see. In 1965, when push-button telephones were brand new and state-of-the-art computers still filled entire rooms, Noyce predicted that the integrated circuit would lead to “portable telephones, personal paging systems, and palm-sized TVs.” His sense of near-limitless possibility led Noyce to pursue technical hunches that his colleagues believed were dead ends. (Often his peers were right, but occasionally, spec

tacularly, they were wrong.) Ideas fell from Noyce like leaves from a tree. For his work to be successful, he had to be surrounded by people who could follow up on his thoughts, filter them, and attend to the detail-work of running a company, because almost as soon as Noyce mentioned an idea, he had left it behind in order to explore another one. Noyce’s peripatetic mental style could be maddening at times. Andy Grove likens it to “a butterfly hopping from thought to thought. Unfinished sentences, unfinished thoughts: you really had to be on your toes to follow him.”7

Noyce was forever pushing people to take their own ideas beyond where they believed they could go. “That’s all you’ve got?” he’d ask. “Have you thought about …” An exchange of this sort left Noyce’s colleagues and employees feeling as though his blue eyes had bored right through their skulls to discover some potential buried inside themselves or their ideas that they had not known existed. It was exhilarating and a bit frightening. “If you weren’t intimidated by Bob Noyce, you’d never be intimidated by anybody,” recalls Jim Lafferty, Noyce’s friend and fellow pilot. “Here is this guy who is so capable in everything he does, and here you are trying to stumble through life and make it look respectable, and now you’re trying to keep up with him. And nobody can keep up with him.”8

Indeed, Noyce can sound too good to be true. He was a brilliant, wealthy, generous, greatly beloved man gifted with enormous vision. But to leave a description of Noyce here would be to sell him short. He was not a superhero. He could be indecisive and would do almost anything to avoid confrontation, a trait that kept him from making difficult decisions and taking tough actions. His resolute focus on the future, his persistent gaze beyond the horizon, left him blind to many details and uninterested in the mundane minutiae of corporate management. This lack of attention had real consequences. He recoiled from strong emotions and would rather pretend a problem did not exist than address it head on. For many years, his personal life was difficult, and he was not entirely without fault in this area.

The Man Behind the Microchip

The Man Behind the Microchip